Working to Code

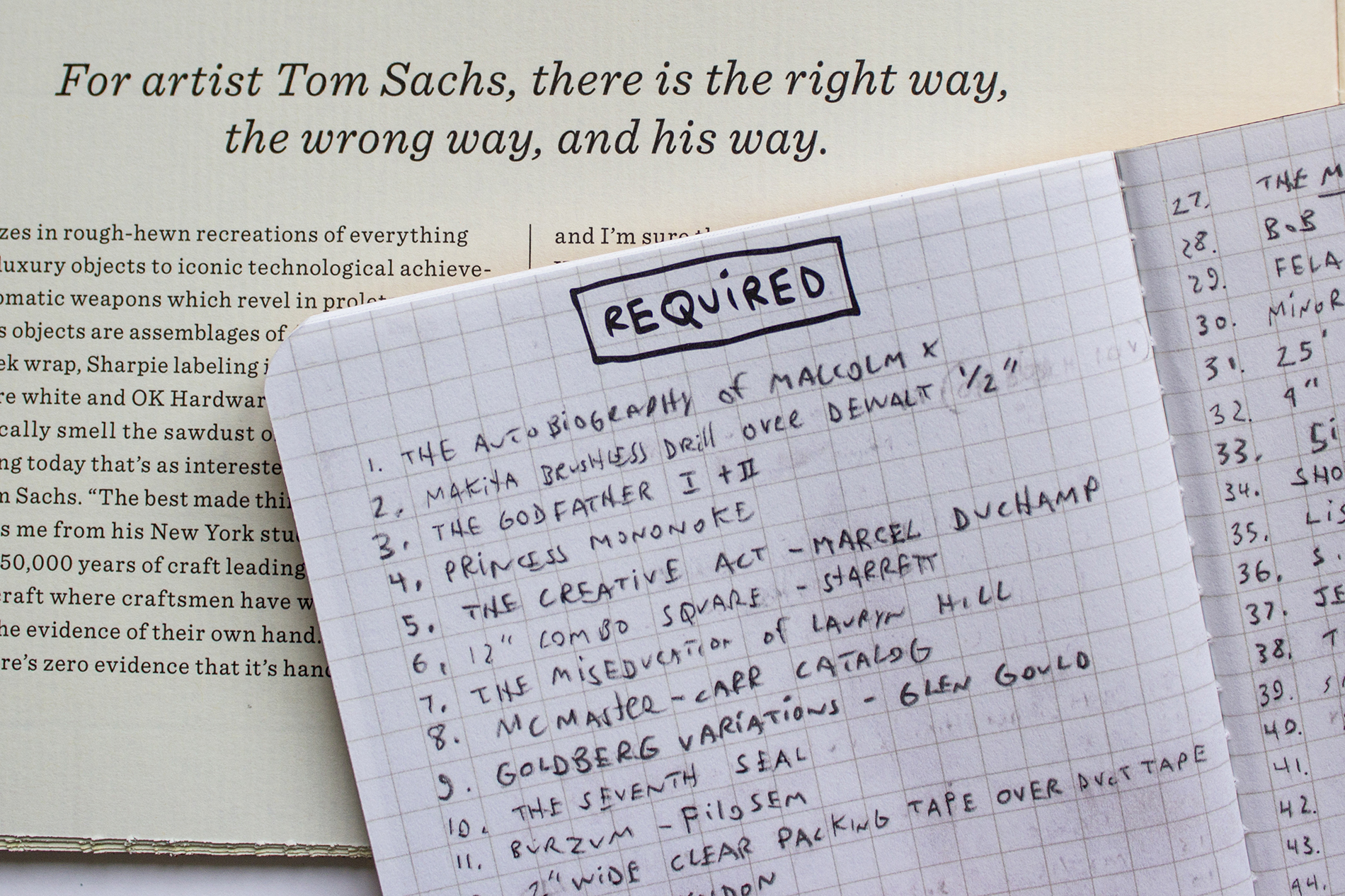

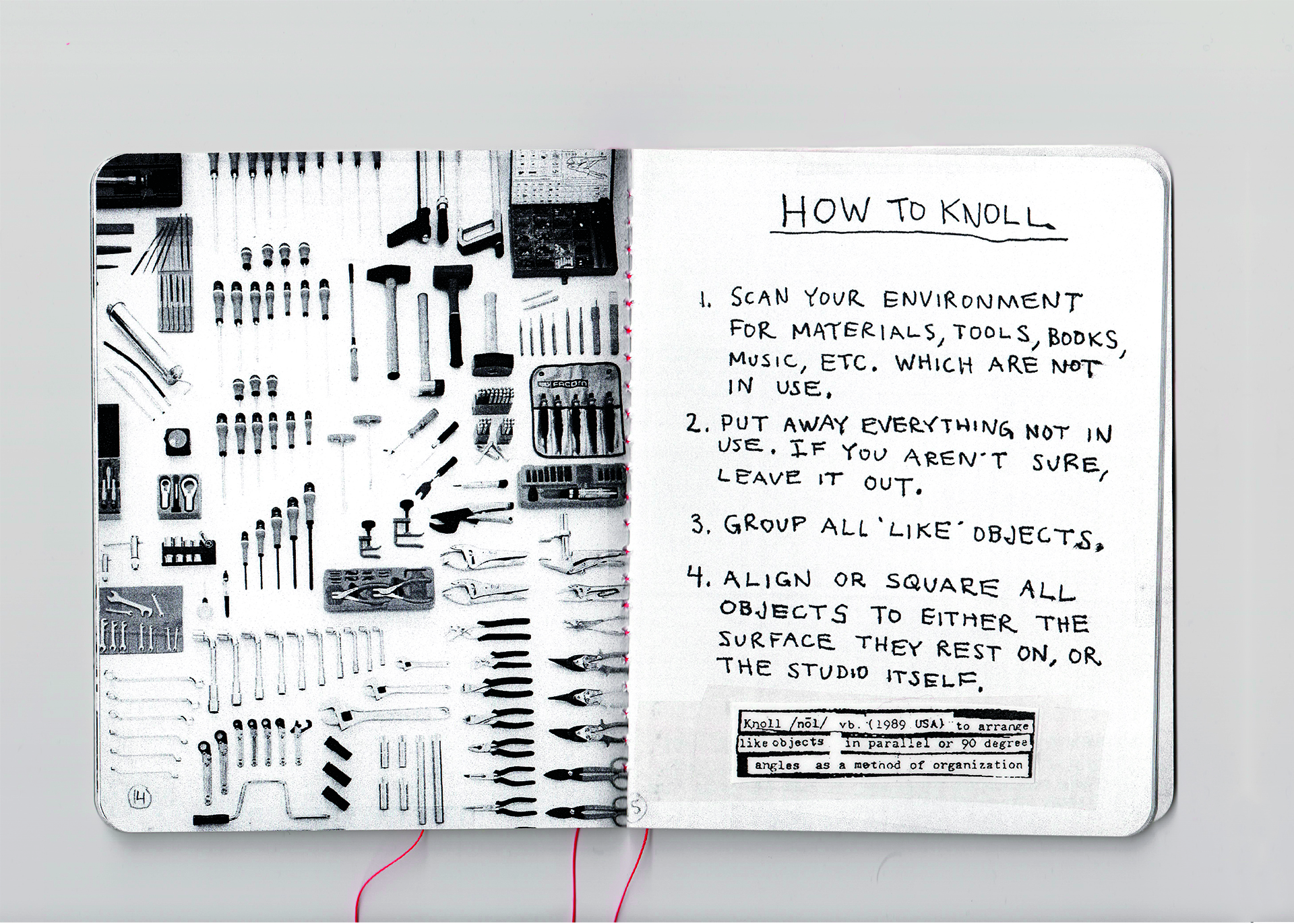

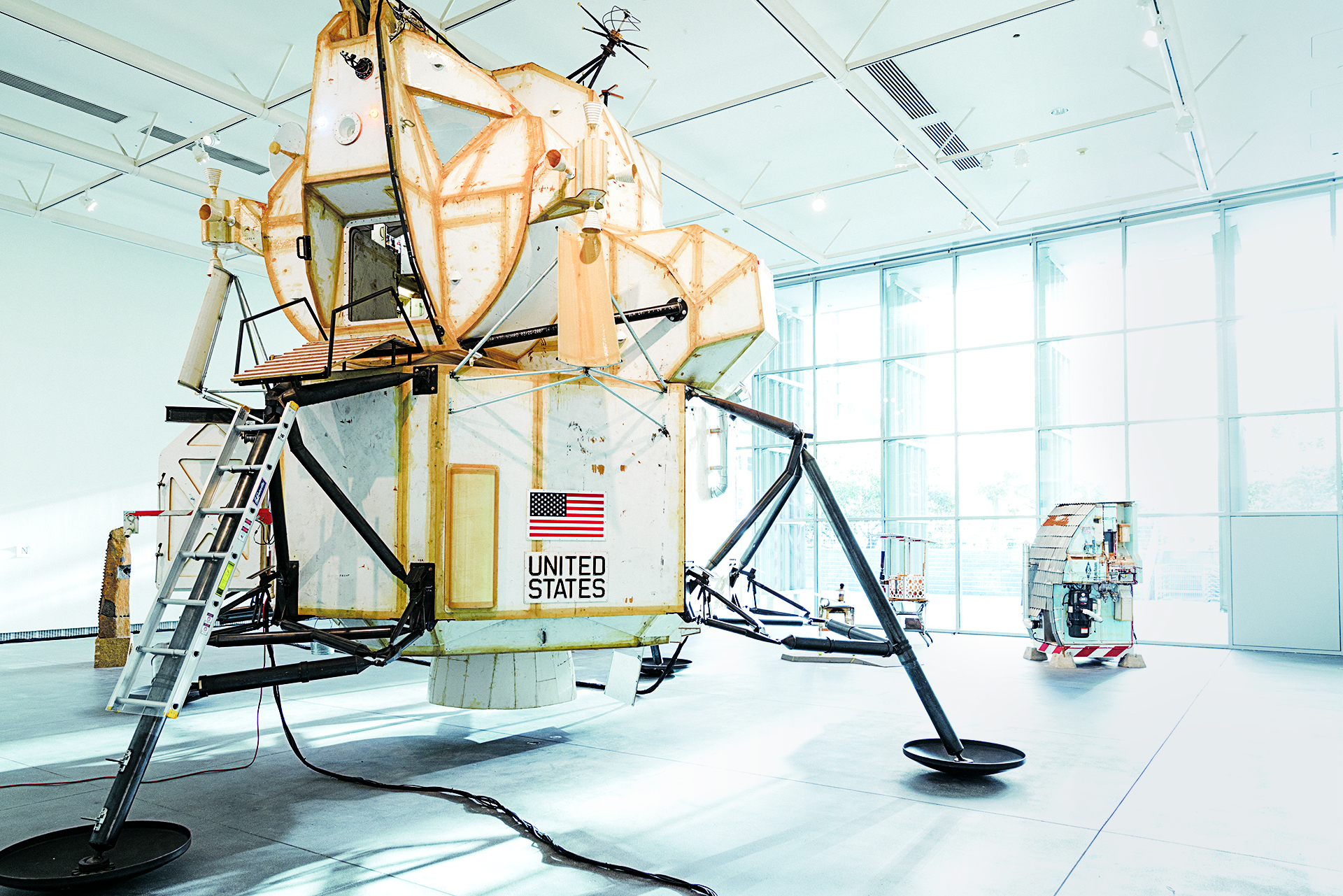

For artist Tom Sachs, there is the right way, the wrong way, and his way. Sachs specializes in rough-hewn recreations of everything from enviable luxury objects to iconic technological achievements and automatic weapons which revel in proletarian materiality.

It helps that Sachs, inspired by the tireless work ethic of James Brown, works seven days and rarely vacations, to his girlfriend’s horror. He views studio maintenance as a sacred charge. As of March, Sachs has a dozen full-time assistants— the studio atmosphere evokes the tight-knit family-like feel of the crew of Steve Zissou’s Belafonte—or a cult. The squad eats red beans and rice every Monday, Louis Armstrong’s recipe. Interns work for three months and if that works out, they take a position. If they’re caught selling a sculpture on eBay, they’re toast.

They even train together. Space Camp is a tongue-in-cheek video demo of the studio team’s morning workout routine “the five” which includes a push-up, a dead-lift, a sit-up, a chin-up and a lunge, all to “strengthen the core.” Each Space Camp session ends with “a meal, hot shower and helicopter rescue simulation,” the latter of which is really a vintage toy game. Sachs maintains that the regime is real and purposeful. “The goal of Space Camp is fitness, preventative medicine. We forge our bodies in the furnace of our souls.”

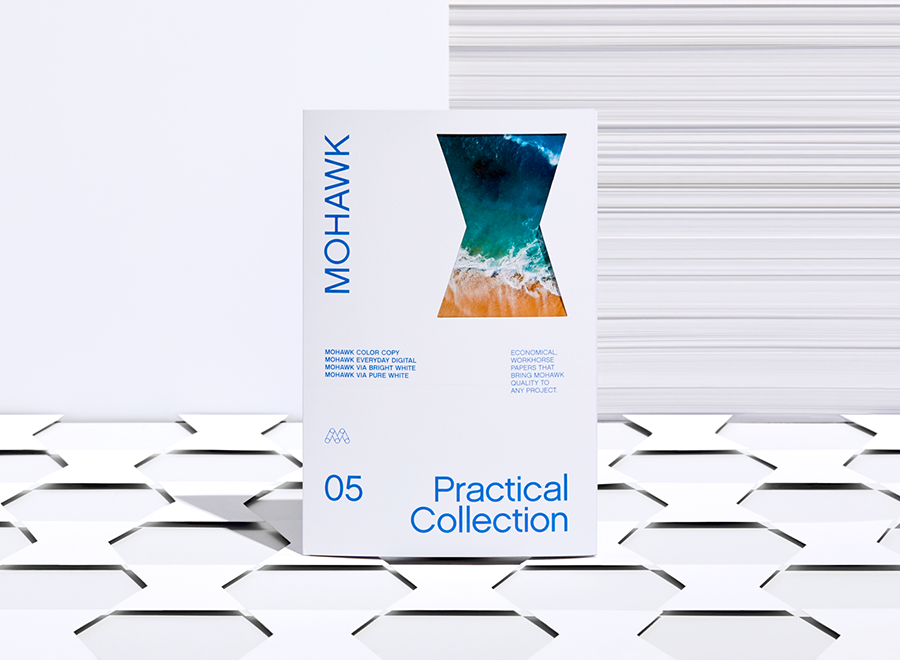

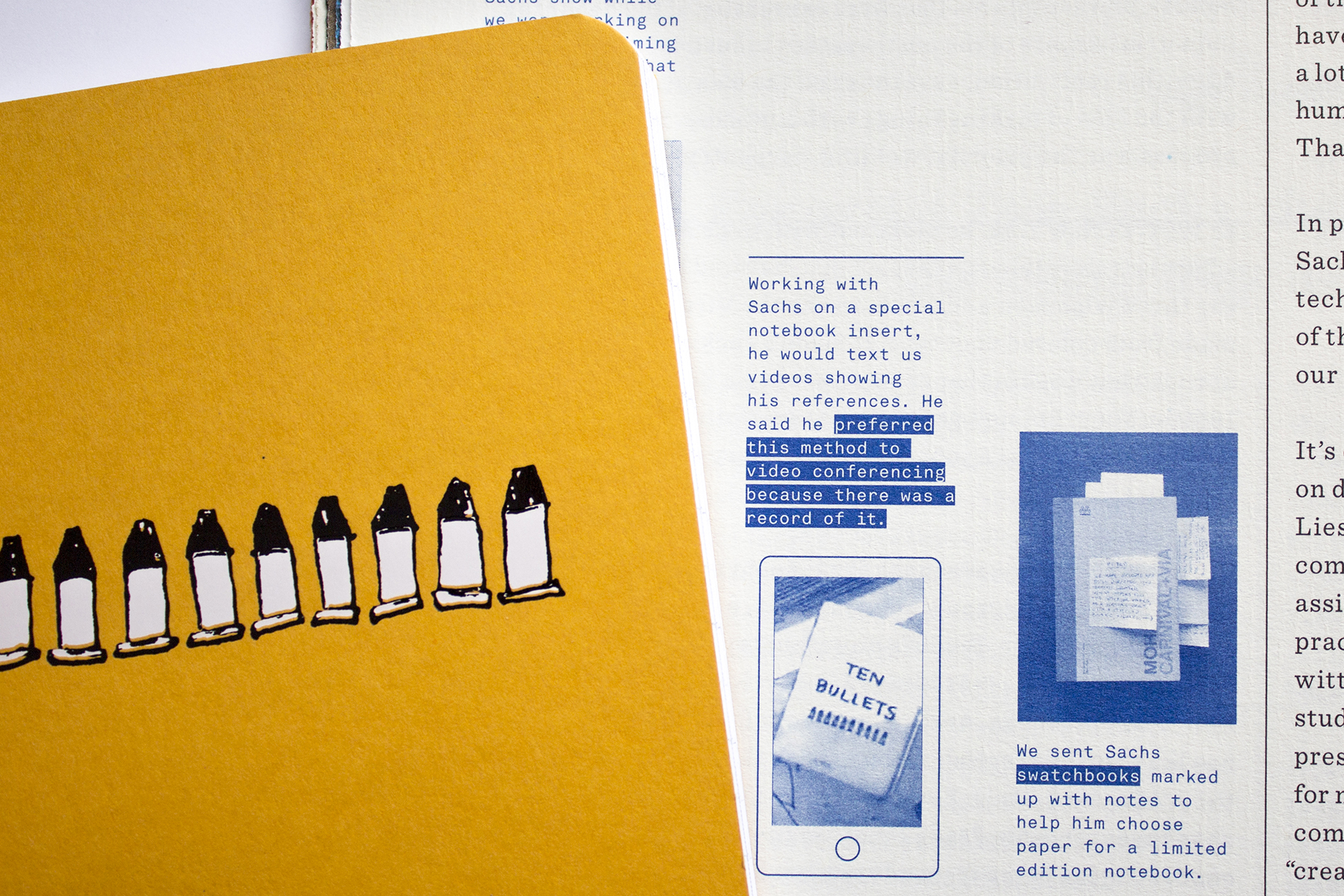

This article was originally published in Issue 11 of the Mohawk Maker Quarterly. The Mohawk Maker Quarterly is a vehicle to support a community of like-minded makers. Content focuses on stories of small manufacturers, artisans, printers, designers, and artists who are making their way in the midst of the digital revolution. Learn more about the quarterly here.

Suggested Articles

As digital printing evolves from compromise to sophisticated tool—advances in color, texture, and fiber papers push the boundaries of what's possible.

In today's competitive marketplace, packaging plays a crucial role in brand perception and consumer satisfaction.

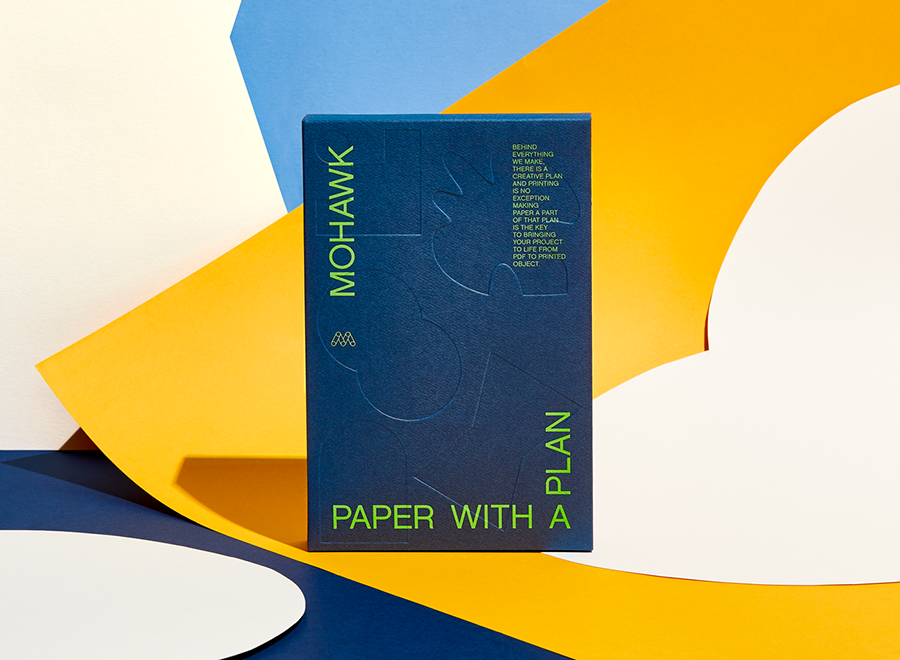

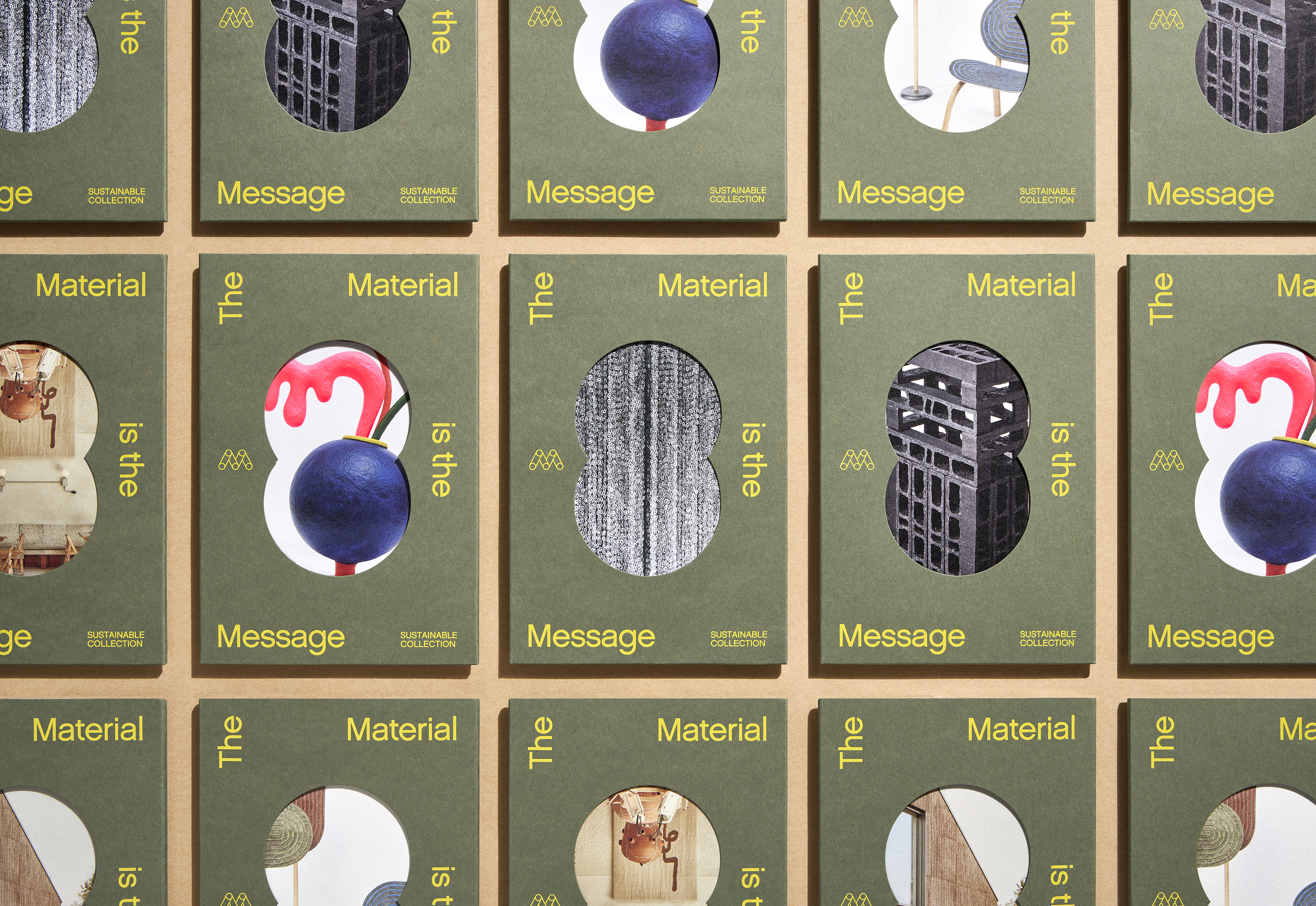

Mohawk Renewal marks a bold new chapter in our ongoing commitment to sustainability and innovation in papermaking.